12 Things Everyone Should Know About IQ

There's a lot of IQ misinformation out there

I had to fly back to New Zealand this week for my Dad’s funeral - so rather than publishing something new for my weekend post, I’m going to republish an old piece. It’s the first in my 12 Things Everyone Should Know series, which focuses on research on IQ. I’ve always been fond of this piece, but because it was one my early posts, many of my current subscribers won’t have seen it. Here, then, is a slightly updated version of the post.

IQ is one of the best-known concepts in psychology, on a par with self-esteem, positive reinforcement, and the Freudian unconscious mind. Everyone is familiar with the term, and everyone seems to have an opinion on the topic.

But like many ideas in psychology, IQ is the subject of a lot of misunderstandings and misinformation. Some believe that IQ tests are basically meaningless - that they don’t measure intelligence in any real sense or tell us anything about IQ-test takers except how good they are at taking IQ tests. Others go further, arguing that IQ research is malign pseudoscience aimed only at justifying discrimination.

None of these claims is true! Psychologists studying IQ have learned a great deal about this form of intelligence over the last century, and have an excellent track record of replicating their results. They know how to measure IQ; they know how nature and nurture help shape IQ; and they know how IQ helps shape people’s lives.

In this post, I’ll outline twelve key findings from IQ research that everyone ought to know. Whether you’re a fan of IQ or a skeptic, I hope you’ll find something here to surprise and challenge you!

1. IQ is one of the most heritable psychological traits – that is, individual differences in IQ are strongly associated with individual differences in genes (at least in fairly typical modern environments). IQ is nearly as heritable as physical traits like height. And the only other psychological traits with similar heritability levels are psychiatric conditions like autism and schizophrenia.

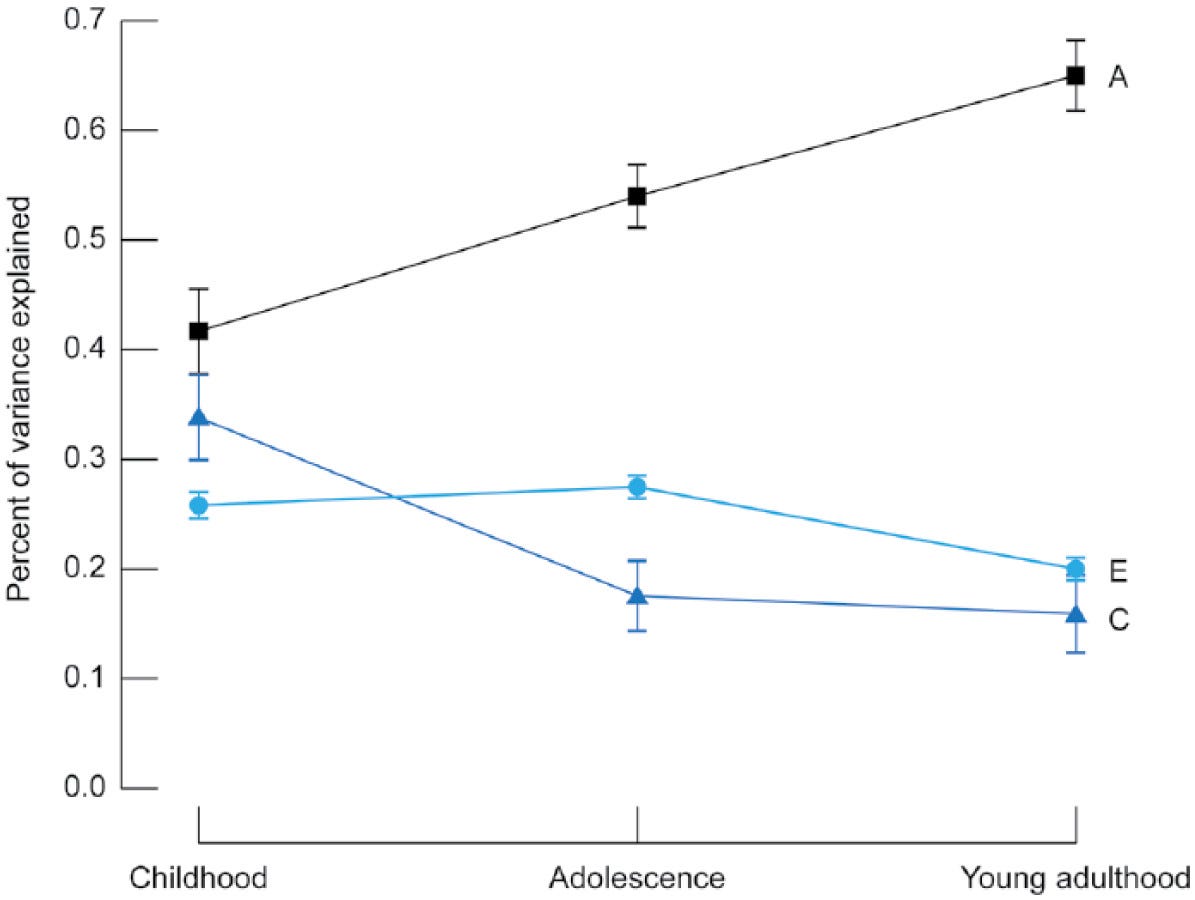

2. The heritability of IQ increases from childhood to adulthood. Meanwhile, the effect of the shared family environment largely fades away. In other words, when it comes to IQ, nature becomes more important as we get older, whereas nurture becomes less. (In the figure below, A = heritability; C = the shared family environment; and E = other environmental influences + random developmental noise and measurement error.)