The Problem of Free Will, Part 3: Does Free-Will Denial Undermine Morality?

Determinism and the death of right and wrong

A man can surely do what he wants to do. But he cannot determine what he wants.

-Arthur Schopenhauer

You think yourself free, because you do what you will; but are you free to will, or not to will; to desire, or not to desire?

-Baron D’Holbach

This is the third and final installment of my three-part series on free will and whether we have it. You can access the full collection here.

In part one, we looked at the two main traditional approaches to the free-will problem: libertarianism (the idea that we’re uncaused causes, steering our own fate) and determinism (the idea that every event is fully determined by its causes and thus set in stone from the earliest moments of the universe). In part two, we turned to compatibilism - the view that free will is perfectly compatible with determinism - and I outlined my own hybrid solution to the problem.

In this final part, we’ll look at what happens to morality if we abandon free will as traditionally conceived. We’ll ask whether we can still hold people responsible for their actions in a deterministic universe. And we’ll ask whether doubting free will turns people bad, leading them to lie, cheat, and steal like there’s no tomorrow.

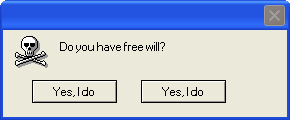

Before we get to any of that, though, a quick quiz:

Kidding! Here’s the real quiz:

I’ll ask these questions again at the end of the essay to see if you’ve changed your mind in the interim - freely or otherwise. Let’s get started!

Freedom and Responsibility

When it comes to free will - and indeed, to most philosophical issues - disagreement is the default setting. People differ on everything from whether we have it, to whether determinism threatens it, to how to even define the term. But if there’s one thing that most combatants seem to agree on, it’s that denying free will would be socially and morally disastrous.

Unsurprisingly, this view is most common among free-will believers. For example, the philosopher Daniel Dennett - a leading exponent of compatibilism - warned that “the doctrine that free will is an illusion is likely to have profoundly unfortunate social consequences if not rebutted forcefully.” But even many free-will skeptics have similar fears and concerns. The philosopher Saul Smilansky, for instance, wrote a book arguing that free will is an illusion, but refuses to give lectures on the topic because he believes that the idea is too dangerous to spread. (I guess he thinks people read even less than they listen.) And Steven Pinker said recently on a podcast that “it would be disastrous if we all believed that [determinism were true and free will were false]. I think it’s a good thing there’s not more common knowledge because I think determinism is true.”

What are the terrible effects that free-will skepticism might unleash? Two in particular stand out. The first is that if we don’t have free will, we could never hold people responsible for their behavior - after all, their behavior was determined and thus ultimately beyond their control. Sure, there might be some personal perks to such a policy; free-will denial would be the ultimate get-out-of-jail-free card. (“Sorry I ran the red light, officer, but my behavior is determined so you can’t give me a ticket.”) The broader implications, however, seem grim. If moral responsibility is an illusion, then we couldn’t blame Hitler, Stalin, or Mao for the atrocities they committed - or, for that matter, praise Jonas Salk, Oskar Schindler, or Norman Borlaug for their moral heroism and the extraordinary good they did for the world.

A second concern is that if people become persuaded that free will is an illusion, they might lose their moral scruples. If we’re not ultimately responsible for our behavior - if we’re just complex biochemical puppets - why bother being good? Why try to resist temptation if the outcome was written in the stars from day one? We might as well just do what we please.

For both reasons, many fear that if belief in free will were to perish, morality would collapse and society would descend into chaos. But does either concern hold water? Let’s consider the arguments.