The Third Law of Behavior Genetics

A lot of variation in psychological traits isn't due to genes or the shared family environment

This is the third part of my five-part series about the Four Laws of Behavior Genetics and why they matter. You can access the full collection here.

In this installment, we’ll look at the Third Law. This is the observation that a big chunk of the variation among individuals in psychological traits isn’t due to genes and isn’t due to the shared family environment. It’s due to… something else. Specifying exactly what that something else is, though, turns out to be one of the most difficult questions in psychology. Will that stop us from trying? Nope! Let’s get started…

The Dark Matter of Behavior Genetics

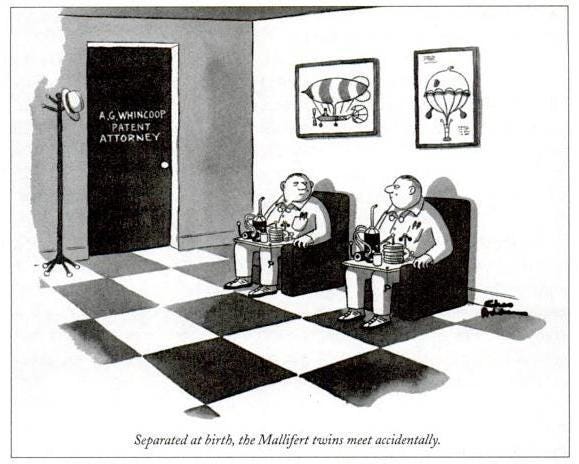

Everyone’s heard stories about identical twins separated at birth and reunited as adults, only to discover that they’re strikingly, almost impossibly similar - not just in how they look but in their personalities and life trajectories.

One of the most famous cases concerns twin brothers known as the Jim twins. At the time they first met as adults, both had jobs in law enforcement, both were interested in carpentry and technical drawing, and both had near-identical smoking and drinking habits. Even more amazing, both had married women called Linda, divorced them, and then married women called Betty!

The phenomenon is captured nicely in this famous cartoon by Charles Addams.

Needless to say, the cartoon exaggerates the effect - as, in fact, do the Jim twins; most identical twins, after all, don’t have the exact same jobs or interests, let alone marry women with the same name. Still, careful research in behavior genetics reveals that genes have a large impact on every psychological trait, from IQ to personality to psychopathology. That’s the First Law of Behavior Genetics, which we covered in the first post in this series.

Individual differences aren’t all down to genes, however; genes explain roughly half the variation in most traits. What explains the rest? Most people, if you ask them, would probably guess that the single-most important contributor is the family home. According to everyday wisdom, people who grow up in the same home - and thus who share the same parents, the same socioeconomic status, and the same neighborhood and schools - will be much more similar to each other than they would if they’d grown up apart. Thus, if the Jim twins and the Mallifert twins had been raised under the same roof, they’d be virtually carbon copies of one another.

That’s the commonsense view, but as so often happens, the commonsense view is wrong. A ton of research in behavior genetics shows that identical twins aren’t much more similar if they grow up together than if they grow up apart. Genes, it seems, have a lot more impact than what’s called the shared environment (defined as everything in the environment that people have in common if they’re raised in the same home). This is the Second Law of Behavior Genetics, which we covered in the second post.

But this leaves us with a mystery. Genes account for roughly half the variation among individuals in psychological traits, but the shared environment accounts for very little, especially by adulthood. That means that there’s a lot of variation that’s not explained by either genes or the shared environment. And that, my friends, is the Third Law of Behavior Genetics, the subject of the present post.

The best evidence for the Third Law - and the best way to summarize what the Law is all about - is the finding that identical twins who grow up together (and thus who share both their genes and the family environment) are not identical. Far from it.

What, then, accounts for the differences?

In a sense, this is an easy question to answer: It’s the part of the environment that people who grow up together don’t have in common. Behavior geneticists call this the nonshared environment.

But what exactly is it in the nonshared environment that matters? Is it differential parental treatment, is it peers, is it random accidents, or what? As mentioned, this has proven to be an extraordinarily difficult question to answer - and to make any meaningful progress toward doing so, we may need to go beyond nature and nurture, and add a third category to our list of what makes us who we are.