Top 10 Daniel Dennett Quotes

My small tribute to a great philosopher

This is the latest in my quotes collection series. Check out the full collection here.

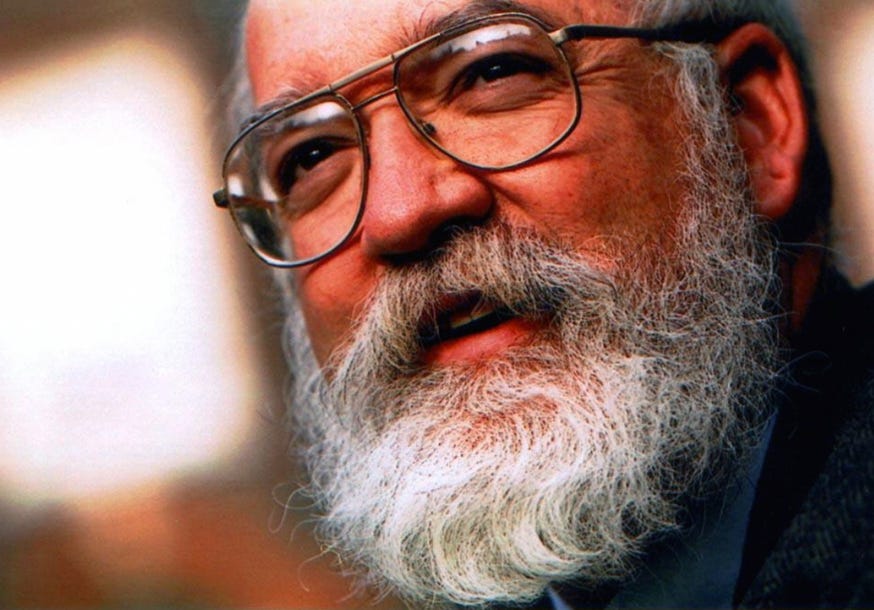

Daniel Dennett, who died earlier this week at the age of 82, was one of the great American philosophers of the last century. He was an iconic figure, once described in The New Yorker as “a cross between Darwin and Santa Claus.” And he was one of my intellectual heroes. As well as being a strong and consistent defender of reason and science, Dennett’s books Consciousness Explained and Darwin’s Dangerous Idea are among my all-time favorites. I didn’t always agree with him, but even when I disagreed, he was always worth reading and mentally sparring with. The following are ten of my favorite Dennett quotes. RIP, Dan.

“Let me lay my cards on the table. If I were to give an award for the single best idea anyone has ever had, I’d give it to Darwin, ahead of Newton and Einstein and everyone else.”

“Comparing our brains anatomically with chimpanzee brains (or dolphin brains or any other nonhuman brains) would be almost beside the point, because our brains are in effect joined together into a single cognitive system that dwarfs all others. They are joined by an innovation that has invaded our brains and no others: language. I am not making the foolish claim that all our brains are knit together by language into one gigantic mind, thinking its transnational thoughts, but, rather, that each individual human brain, thanks to its communicative links, is the beneficiary of the cognitive labors of the others in a way that gives it unprecedented powers.”

“The best reason for believing that robots might some day become conscious is that we human beings are conscious, and we are a sort of robot ourselves.”

“Not a single one of the cells that compose you knows who you are, or cares.”

“There is a species of primate in South America more gregarious than most other mammals, with a curious behavior. The members of this species often gather in groups, large and small, and in the course of their mutual chattering , under a wide variety of circumstances, they are induced to engage in bouts of involuntary, convulsive respiration, a sort of loud, helpless, mutually reinforcing group panting that sometimes is so severe as to incapacitate them. Far from being aversive, however, these attacks seem to be sought out by most members of the species, some of whom even appear to be addicted to them... the species is Homo sapiens (which does indeed inhabit South America, among other places), and the behavior is laughter.”

“‘A zebra which has caught sight of a lion does not forget where the lion is when it stops watching the lion for a moment. The lion does not forget where the zebra is’ (Margolis, 1987, p. 53). Compare this to the simpler phenomenon of the sunflower that tracks the passage of the sun across the sky, adjusting its angle like a movable solar panel to maximize the sunlight falling on it. If the sun is temporarily obscured, the sunflower cannot project the trajectory; the mechanism that is sensitive to the sun’s passage does not represent the sun’s passage in this extended sense. The beginnings of real representation are found in many lower animals (and we should not rule out, a priori, the possibility of real representation in plants), but in human beings the capacity to represent has skyrocketed.”

“Postmodernism, the school of ‘thought’ that proclaimed ‘There are no truths, only interpretations’ has largely played itself out in absurdity, but it has left behind a generation of academics in the humanities disabled by their distrust of the very idea of truth and their disrespect for evidence, settling for ‘conversations’ in which nobody is wrong and nothing can be confirmed, only asserted with whatever style you can muster.”

“You watch an ant in a meadow, laboriously climbing up a blade of grass, higher and higher until it falls, then climbs again, and again, like Sisyphus rolling his rock, always striving to reach the top. Why is the ant doing this? What benefit is it seeking for itself in this strenuous and unlikely activity? Wrong question, as it turns out. No biological benefit accrues to the ant. It is not trying to get a better view of the territory or seeking food or showing off to a potential mate, for instance. Its brain has been commandeered by a tiny parasite, a lancet fluke (Dicrocelium dendriticum), that needs to get itself into the stomach of a sheep or a cow in order to complete its reproductive cycle. This little brain worm is driving the ant into position to benefit its progeny, not the ant’s… Does anything like this ever happen with human beings? Yes indeed. We often find human beings setting aside their personal interests, their health, their chances to have children, and devoting their entire lives to furthering the interests of an idea that has lodged in their brains.”

“I am not joking when I say that I have had to forgive my friends who said that they were praying for me. I have resisted the temptation to respond ‘Thanks, I appreciate it, but did you also sacrifice a goat?’”

“The secret of happiness is: Find something more important than you are and dedicate your life to it.”

Bonus Dennett Content: Dennett generally wrote straight philosophy, but he also once wrote a very entertaining philosophical short story called “Where am I?” In this quirky little piece, neuroscientists removed Dennett’s brain and placed it in a vat, hooked up with microminiaturized radio transceivers so that he could remotely control his body. Whether you’re a philosophile or just philosophy-curious, I’d recommend giving the story a whirl; it’s a lot of fun. Here’s an excerpt.

“I gather the operation was a success,” I said. “I want to go see my brain.” They led me (I was a bit dizzy and unsteady) down a long corridor and into the life-support lab. A cheer went up from the assembled support team, and I responded with what I hoped was a jaunty salute. Still feeling lightheaded, I was helped over to the life-support vat. I peered through the glass. There, floating in what looked like ginger ale, was undeniably a human brain, though it was almost covered with printed circuit chips, plastic tubules, electrodes, and other paraphernalia. “Is that mine?” I asked. “Hit the output transmitter switch there on the side of the vat and see for yourself,” the project director replied. I moved the switch to OFF, and immediately slumped, groggy and nauseated, into the arms of the technicians, one of whom kindly restored the switch to its ON position. While I recovered my equilibrium and composure, I thought to myself: “Well, here I am sitting on a folding chair, staring through a piece of plate glass at my own brain… But wait,” I said to myself, “shouldn’t I have thought, ‘Here I am, suspended in a bubbling fluid, being stared at by my own eyes’?” I tried to think this latter thought. I tried to project it into the tank, offering it hopefully to my brain, but I failed to carry off the exercise with any conviction. I tried again. “Here am I, Daniel Dennett, suspended in a bubbling fluid, being stared at by my own eyes.” No, it just didn’t work. Most puzzling and confusing. Being a philosopher of firm physicalist conviction, I believed unswervingly that the tokening of my thoughts was occurring somewhere in my brain: yet, when I thought “Here I am,” where the thought occurred to me was here, outside the vat, where I, Dennett, was standing staring at my brain.

Coming Soon…

I recently went on the Modern Wisdom podcast with the great Chris Williamson. We had a fun, wide-ranging conversation, which I’ll make available via the newsletter soon. Stay tuned!

Follow Steve on Twitter/X.

To support my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. This will get you: (1) full access to all new posts and the Archive, (2) full access to my “12 Things Everyone Should Know” posts, Linkfests, and other regular features, and (3) the ability to post comments and interact with the N3 Newsletter community. Thanks!

I love Dennett since I read "Darwin's Dangerous Idea." However, I was a bit disappointed at his autobiography. He spends way too much time talking about the impressive people he met (Fellini, Hilary Putnam etc.). That's fine for some cool anecdotes, but he mentions his mother's passing, for instance, very quickly and gets back to it. Now that's just weird.

I'll offer up a favorite Dennett quote as well, from Kinds of Minds: Toward An Understanding of Consciousness

"We intentional systems do sometimes desire evil, through misunderstanding or misinformation or sheer lunacy, but it is part and parcel of rationality to desire what is deemed good. It is this constitutive relationship between the good and the seeking of the good that is endorsed—or rather enforced—by the natural selection of our forebears: those with the misfortune to be genetically designed so that they seek what is bad for them leave no descendants in the long run."

This idea was a revelation for me and changed my approach to understanding others' motives, especially of people who I think act irrationally or do things I don't agree with or understand.

Rather than judge a person (fundamental attribution error) or their behavior, I try to understand why they think their behavior is good for them. I may not always agree with the thinking, but I have a more them-centered (vs. me-centered) understanding of their motives to work off of.