Pets as Substitute Children

An evolutionary perspective on our love of other animals and our habit of keeping pets

In Case You Missed It…

Humans have a curious relationship with our pets. Sometimes they’re companions; sometimes they’re protectors; sometimes, they’re therapists or even status symbols. In many cases, though, they seem to play a deeper role: They function as substitute children.

Here are two fascinating findings - and two graphs - that fit nicely with this idea.

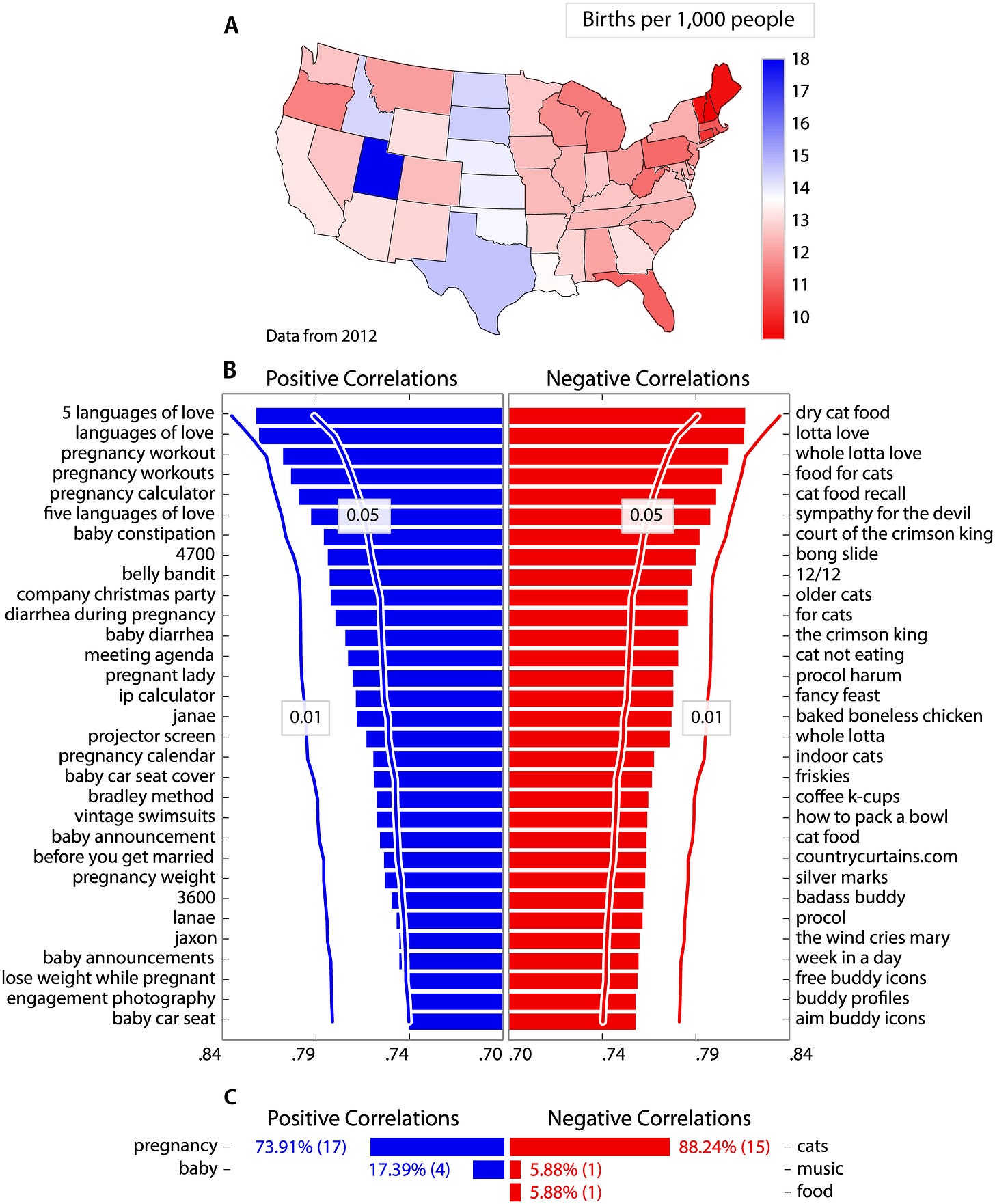

The first is that in US states with higher birth rates, people do more Google searches for pregnancy, whereas in states with lower birth rates, they do more searches for cats.

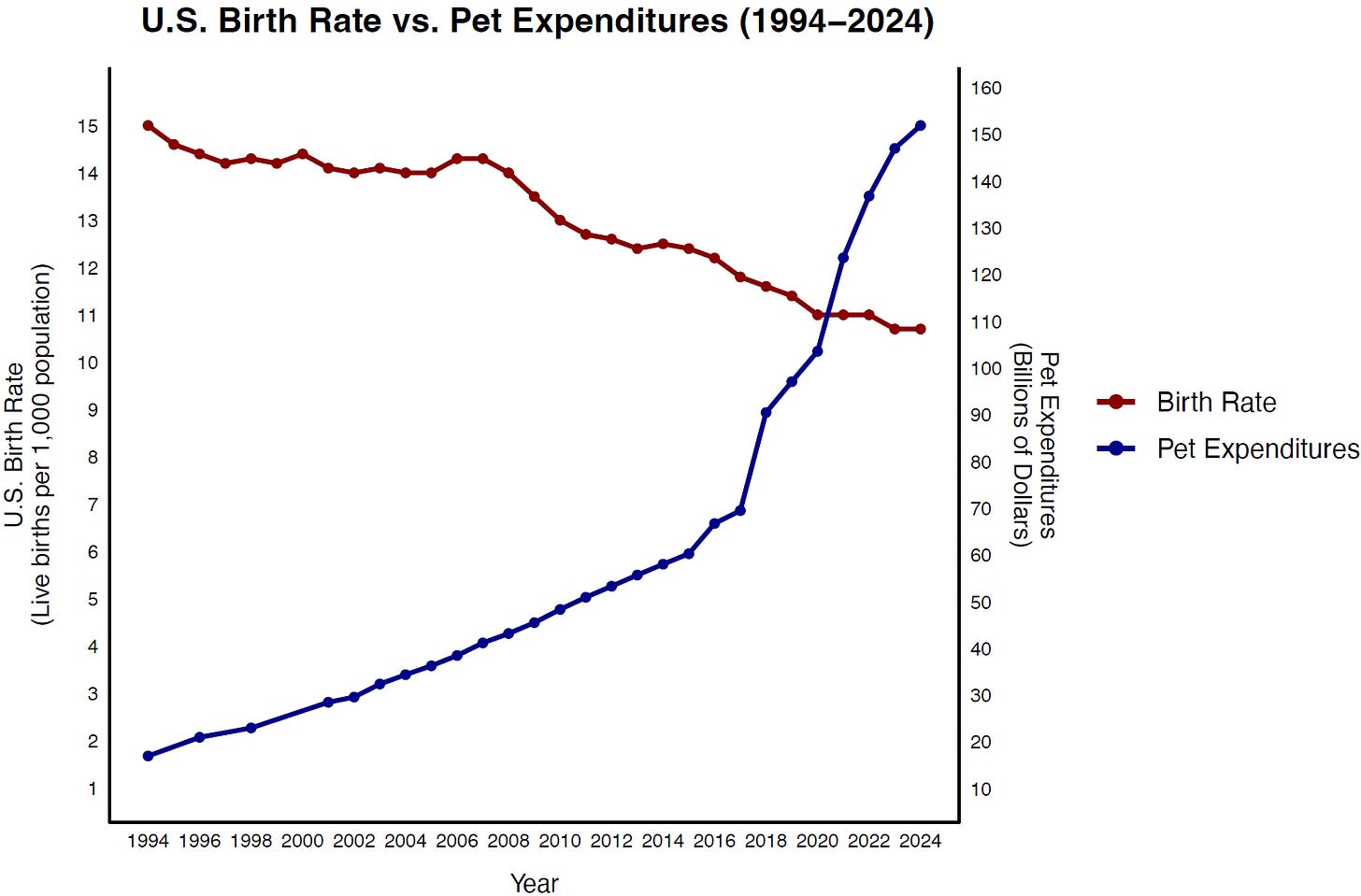

The second finding is that, as the US birth rate has gone down in the last three decades, spending on pets has skyrocketed.

Both patterns are exactly what we’d expect if pets sometimes take the place of children in people’s lives.

I explored our love of other animals, and our zoologically weird habit of keeping pets, in my book The Ape That Understood the Universe. Here’s an excerpt from Chapter 2, where I discuss our online obsession with cat videos, dog videos, and the like.

[Pornography is] not our only evolutionarily puzzling online behavior. Another is our addiction to photos and videos of cute baby animals. The Internet is saturated with kittens, puppies, and baby orangutans in wheelbarrows. Why do so many people take such delight in staring at infant members of other species? It’s not as if, say, porcupines enjoy staring at baby chickens. As with porn, our love of these nonhuman animals is probably not an adaptation. More than likely, it’s spillover from psychological mechanisms designed for more human-centered purposes. There’s a certain cluster of traits that people everywhere find irresistibly cute. This includes big round eyes in the center of the face, a small nose, and plump, stubby limbs. Our affection for creatures with these features presumably evolved to motivate us to care for our own infants and toddlers. But the same features are found in many other infant mammals, and even in the adult members of some nonhuman species. As a result, we often feel affectionate and protective toward these individuals as well – not because it’s adaptive, but just because adaptations aren’t perfect. By the way, as you might already have noticed, the spillover hypothesis doesn’t just explain our fondness for cute animal videos. It also hints at an explanation for a much older and more pervasive phenomenon: our habit of keeping pets.

…and here’s an excerpt from Chapter 4 where I discuss the idea that pet-keeping is in part a byproduct of our evolved fondness for infant faces (known as the Kindchenschema).

Our love of infantile faces has a number of interesting side effects. One… is that we don’t just find our own babies cute; we find babies of other species cute as well. Roughly speaking, other animals’ cuteness is proportional to their resemblance to human offspring. It’s rare to hear people say “Aww, what a cute baby worm” or “That’s the most adorable baby scorpion I’ve ever seen.” But most people are suckers for baby mammals, which are far more closely related to us and thus far more similar. Not only that, but we’re suckers for adult mammals that have baby-like faces: flat-faced cats, for instance, as opposed to pointy-faced opossums. Our love of these furry nonhumans is probably not an adaptation in itself; more than likely, it’s spillover from the Kindchenschema. It’s also a big part of the explanation for one of our strangest habits: our habit of keeping pets. People have many kinds of relationships with their pets; pets can be friends or protectors, servants or tools. Often, though, pets play the role of surrogate children. Where that’s the case, pet keeping is a byproduct of our unique parental instincts.

You can read the Google-searches paper for free here.

You can read the spending-on-pets paper for free here. (Thanks to Rob Henderson for putting me onto it.)

And you can read the first chapter of my book The Ape That Understood the Universe for free here.

Follow me on Twitter/X for more psychology, evolution, and science.

Coming Soon to The Nature-Nurture-Nietzsche Newsletter…

The Problem of Free Will, Part 2: Determined to Be Free (check out Part 1 here)

12 Things Everyone Should Know About Evolutionary Theory (check out the rest of the “12 Things Everyone Should Know” series here)

Beyond g: The Genetics of Specific Cognitive Abilities

How You Can Support the Newsletter

If you like what I’m doing with The Nature-Nurture-Nietzsche Newsletter, and want to support independent science writing, there are several ways you can do it.

Like and Restack: Click the buttons at the top or bottom of the page to boost the post’s visibility on Substack.

Share: Send the post to friends or share it with your followers on social media. The post is free to read for all, so they won’t hit a paywall.

Upgrade to Paid: A paid subscription gets you:

If you could do any of the above, I’d be hugely grateful. The support of readers like you helps keep this newsletter going and growing. Thanks so much!

Steve Stewart-Williams

I just try to use my children as status symbols to check all the boxes… haha

Really interesting evolutionary take on how adaptions are clear cut in particular domains. Makes a lot of sense.

Have had your books on my list for a while but I’m encouraged to move them to the top of the list the more I dive into your work.