Sex Differences in Work Preferences, Life Values, and Personal Views

...and how they shape men and women's lives

I’m travelling at the moment, so I’m taking the opportunity to reshare one of the most popular early posts from The Nature–Nurture–Nietzsche Newsletter. Hope you enjoy it!

What determines men and women’s life outcomes - the professions they go into, the goals they set themselves, the time they devote to career versus family? The short answer, of course, is “Lots of things.” But according to a recent paper by David Lubinski and colleagues, among the most important contributors are people’s work preferences, life values, and personal views. And because these things aren’t evenly distributed across the sexes, they may help to explain certain sex differences in people’s life outcomes.

Women’s place in the world has radically transformed over the last half-century. In some ways, in fact, women in the West are now doing better than men. Among other things, more women than men are graduating from high school, more women are going to university, and more women are getting PhDs.

At the same time, however, women are still underrepresented in certain fields, including, most famously, inorganic STEM fields such as computer science, engineering, and physics. (STEM, as I’m sure you know, stands for science, technology, engineering, and math.) On top of that, women are underrepresented at the highest levels of most fields - including those in which women outnumber men overall. What explains these stubborn gender gaps?

Three commonly cited contributors are:

Bias and barriers

Sex differences in career-relevant interests (e.g., the fact that more men than women are interested in working with things, whereas more women than men are interested in working with people)

Sex differences in cognitive profiles (the fact, for instance, that more men than women exhibit math tilt [math > verbal, which predicts going into inorganic STEM fields], whereas more women than men exhibit verbal tilt [verbal > math, which predicts going into non-STEM fields])

Less often discussed is the role of sex differences in work preferences, life values, and personal views. These are the differences that Lubinski, Camilla Benbow, Kira McCabe, and Brian Bernstein decided to explore in their new paper “Composing Meaningful Lives: Exceptional Women and Men at Age 50,” published in the journal Gifted Child Quarterly.

The two lead authors, Lubinski and Benbow, are most famous for their research tracking a group of individuals identified as mathematically gifted as children. In this paper, they and their collaborators focused the microscope on two subsamples from within that broader group. The first was individuals who did STEM PhDs at top-ranked universities. The second was individuals who were identified at age 12 as not merely gifted or highly gifted, but as profoundly gifted - that is, in the top 0.01% of ability. In both cases, these are people who, more than almost anyone else in the world, have the power to create the lives and careers they most want. As such, exploring sex differences in their work preferences, life values, and personal views may be particularly instructive.

Enough preamble; let’s get to the results!

Sex Differences in Work Preferences

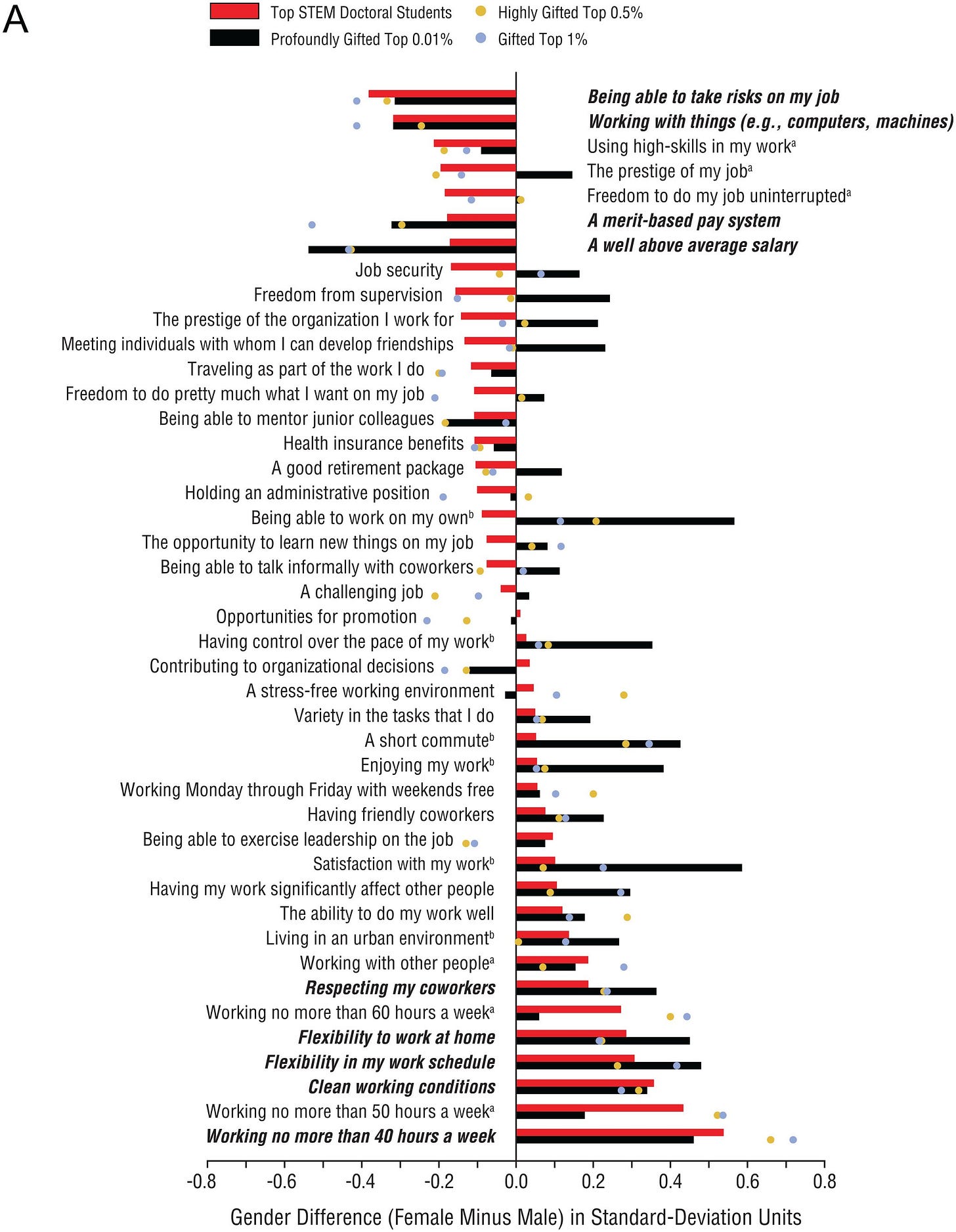

The main results are captured in the following three figures. The first shows sex differences in work preferences in the two main samples, along with two benchmark samples from Lubinski and Benbow’s earlier research: the gifted (top 1%) and the highly gifted (top 0.5%).

Scores below 0 indicate that, on average, the item was endorsed more strongly by men than women; scores above 0 indicate that the item was endorsed more strongly by women than men. Items in bold were statistically significant for both the two main samples: the top STEM doctoral students and the profoundly gifted.

As you can see, men on average put more value on taking risks in their jobs, working with things, having a merit-based pay system, and earning a high salary. Women, in contrast, put more value than men on job flexibility, being able to work from home, and working no more than 40 hours a week.

Sex Differences in Life Values

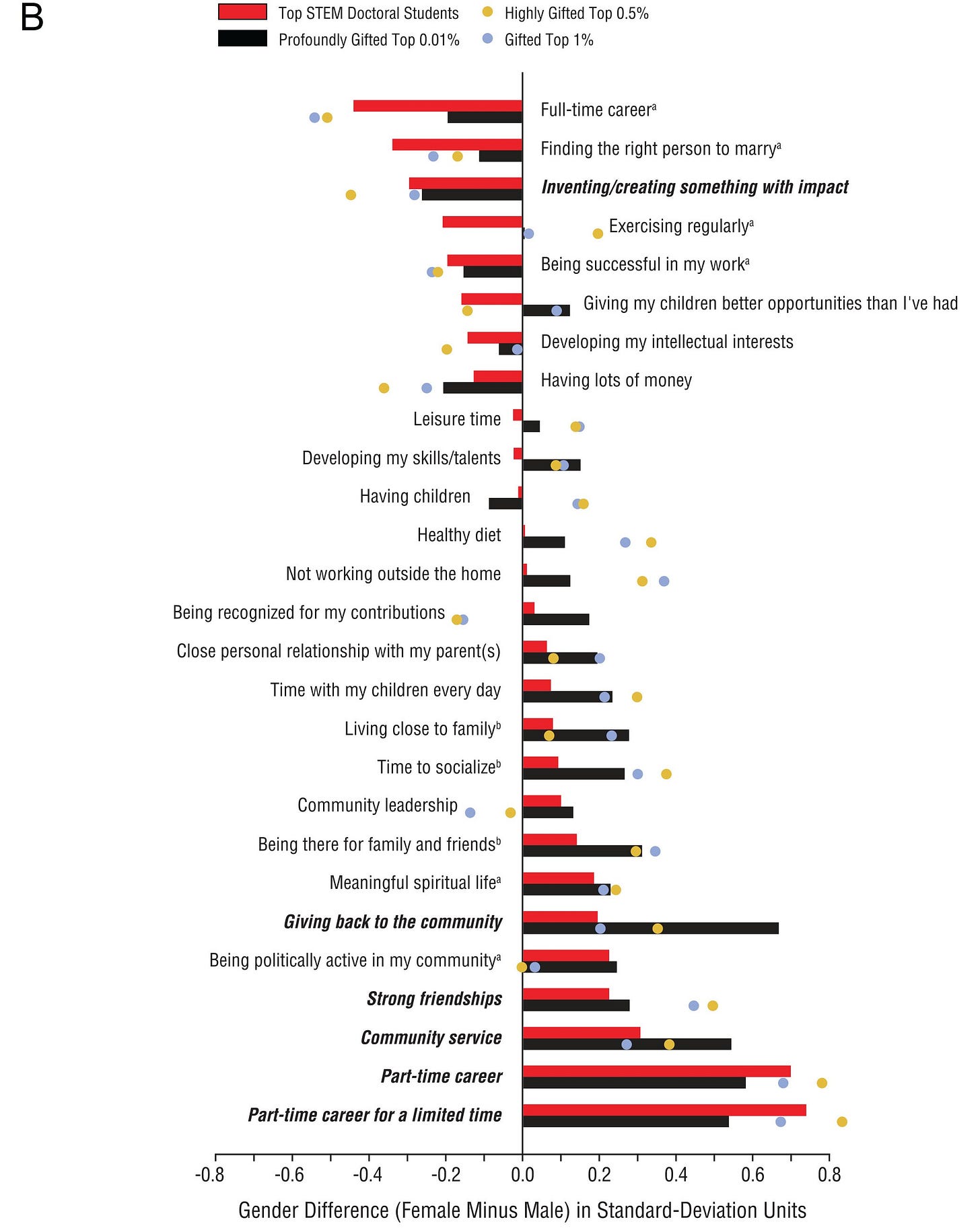

The next figure shows sex differences in life values. Again, scores lower than 0 indicate that men value the item more than women, whereas scores above 0 indicate that women value it more than men.

Among the most notable findings are that men put a greater premium on inventing or creating something that has a big impact, whereas women put a greater premium on giving back to the community, having strong friendships, and being able to work part-time.

Sex Differences in Personal Views

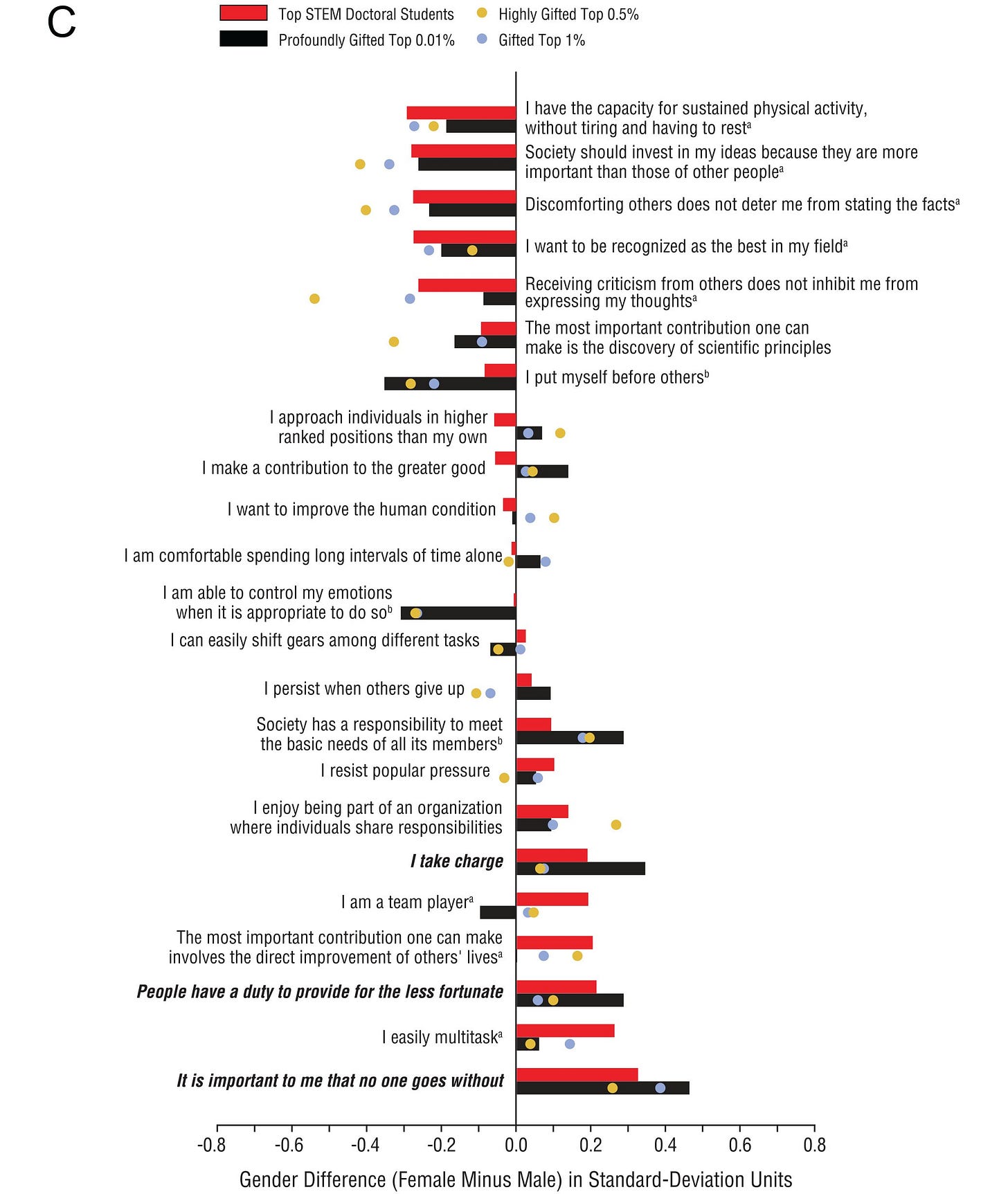

The third figure in the series shows sex differences in personal views. Among other things, we see that men were more likely to agree that society should invest in their ideas because their ideas are more important than other people’s, and that making others uncomfortable doesn’t deter them from stating the facts. Women, on the other hand, were more likely to agree that they take charge, that people have a duty to look after the less fortunate, and that it’s important to them that no one goes without.

Different Paths; Same Destination

Here’s how Lubinski et al. summed up their findings:

Collectively, men prioritized their personal advancement, making money, and advancing society through knowledge creation, inventing material products, or leading impactful careers; women, while also finding those endeavors to be important, gave more precedence to keeping society healthy and vibrant.

Based on their somewhat different preferences and priorities, argued the authors, the men and women in the study created somewhat different lives for themselves. Most notably, men invested more time than women into their careers, whereas women invested more time than men into family and community. These are average differences, of course, not categorical ones; plenty of women devoted more time to their careers than plenty of men, and vice versa for men and their families. Still, the average differences weren’t trivial, and they presumably help explain why, on average, the men did better in terms of traditional career-related success indicators - and, at the same time, why women presumably did better in terms of often-overlooked and undervalued indicators, such as giving back to the community.

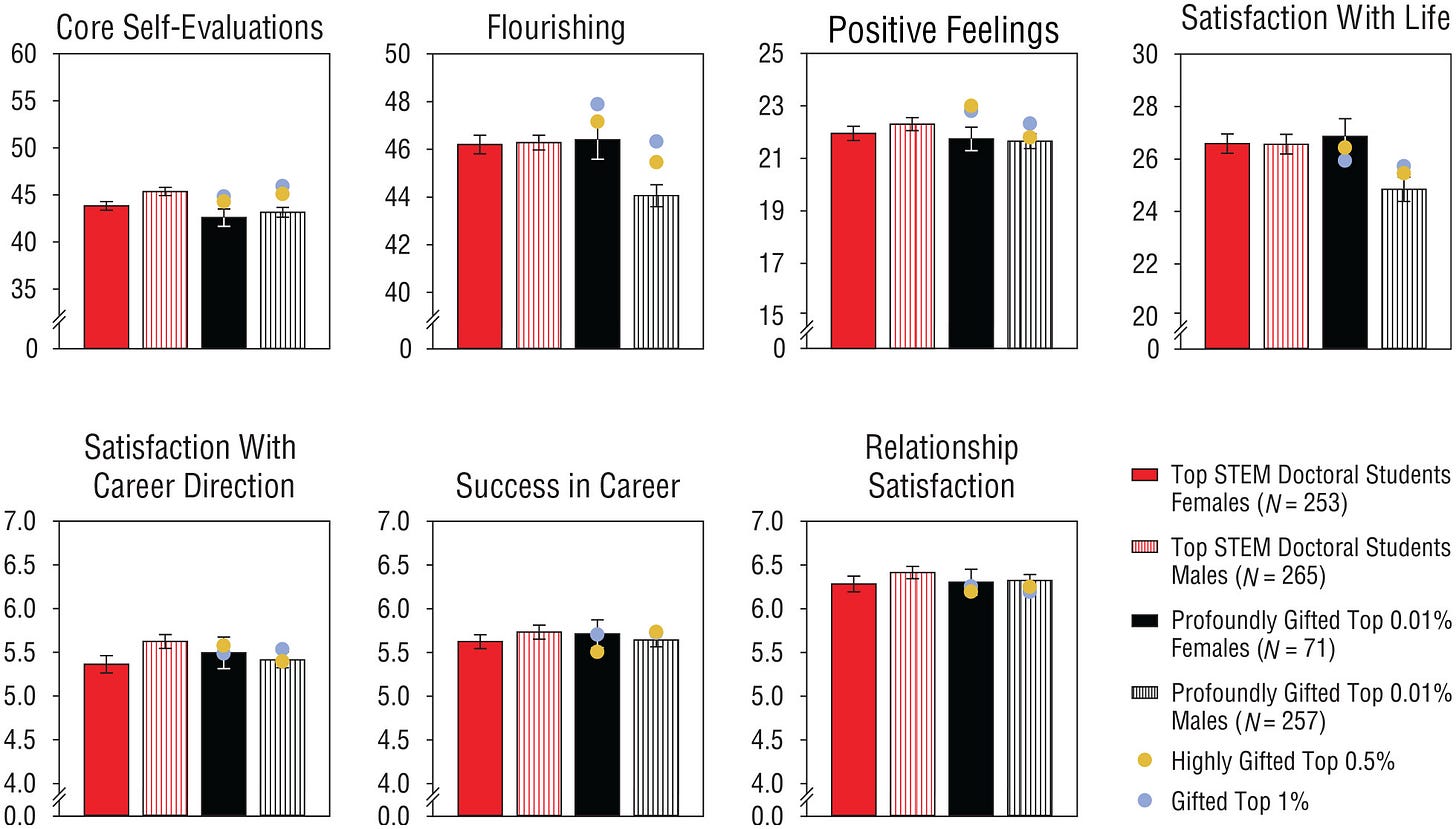

How happy were men and women with the lives they’d created? The figure below addresses this important question. It shows that both sexes were generally happy with their careers, their relationships, and their lives overall - and more importantly for present purposes, that the sexes didn’t particularly differ in how happy they were in any of these areas. In Lubinski and co.’s view, this is because men and women had managed to create lives for themselves that meshed well with their somewhat different preferences and priorities.

None of this is to suggest, by the way, that gender discrimination has fully evaporated, or that it plays no role in shaping current gender gaps. What it does suggest, however, is that to the extent that men and women’s life outcomes are shaped by sex differences in work preferences, life values, and personal views, discrimination plays a smaller role in shaping those outcomes than we might otherwise suspect.

Of course, some would argue that these sex differences are themselves products of sexist socialization, and thus are indirectly discriminatory. The question of the origins of the differences is a complex one, and I can’t deal with it in detail here. I will say two things, though. First, we shouldn’t be too confident that the differences are 100% due to socialization; some evidence suggests that there’s an innate contribution as well. And second, wherever the differences come from, once they’re in place, people are presumably going to be happier if they can act freely on those preferences than if roadblocks are put in their way by policymakers seeking to nullify gender gaps. If we want to try to equalize things, the appropriate place to intervene would seem to be when people’s preferences and values are forming, rather than at the point where people are making decisions about what they want to do with their lives.

The Lubinski paper is open access, so you can read it here for free.

Follow me on Twitter/X for more psychology, evolution, and science.

Upgrade to a Paid Subscription

If you enjoyed this piece, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid support makes it possible for me to keep writing essays like this one - and it gives you access to all past and future subscriber-only posts.

Either way, thanks for reading and sharing. It really helps the newsletter reach new people who might enjoy it too.

Coming Soon to The Nature-Nurture-Nietzsche Newsletter…

12 Things Everyone Should Know About the Dark Triad

The Problem of Free Will, Part 3: Does Determinism Make Us Bad?

Personality, Intelligence, and Success

Further Reading

Several of my academic papers deal with the question of sex differences in STEM. You can read them for free on ResearchGate. Here are the two main ones, which were co-authored with Lewis Halsey.

Stewart-Williams, S., & Halsey, L. G. (2021). Men, women and STEM: Why the differences and what should be done? European Journal of Personality, 35, 3-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890207020962326

Stewart-Williams, S., & Halsey, L. G. (2022). Not biology or culture alone: Response to El-Hout et al. (2021). European Journal of Personality, 36, 991–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070211022477

"Inorganic STEM" is a term I haven't encountered. Does it mean STEM excluding biology? STEM fields requiring some advanced use of mathematics?