Testing the IQ Threshold Hypothesis

Even among the top 1%, higher IQ predicts greater achievement

As I mentioned in an earlier post, IQ predicts achievement: People with higher IQs tend to do somewhat better in education and on the job than their lower-IQ peers. But is this true at every level of IQ?

According to a widespread view, the answer is no. Beyond a certain point - most often, an IQ of 120 - the benefits of IQ supposedly plateau, and having a higher IQ is no longer associated with any greater achievement. This idea is known as the threshold hypothesis.

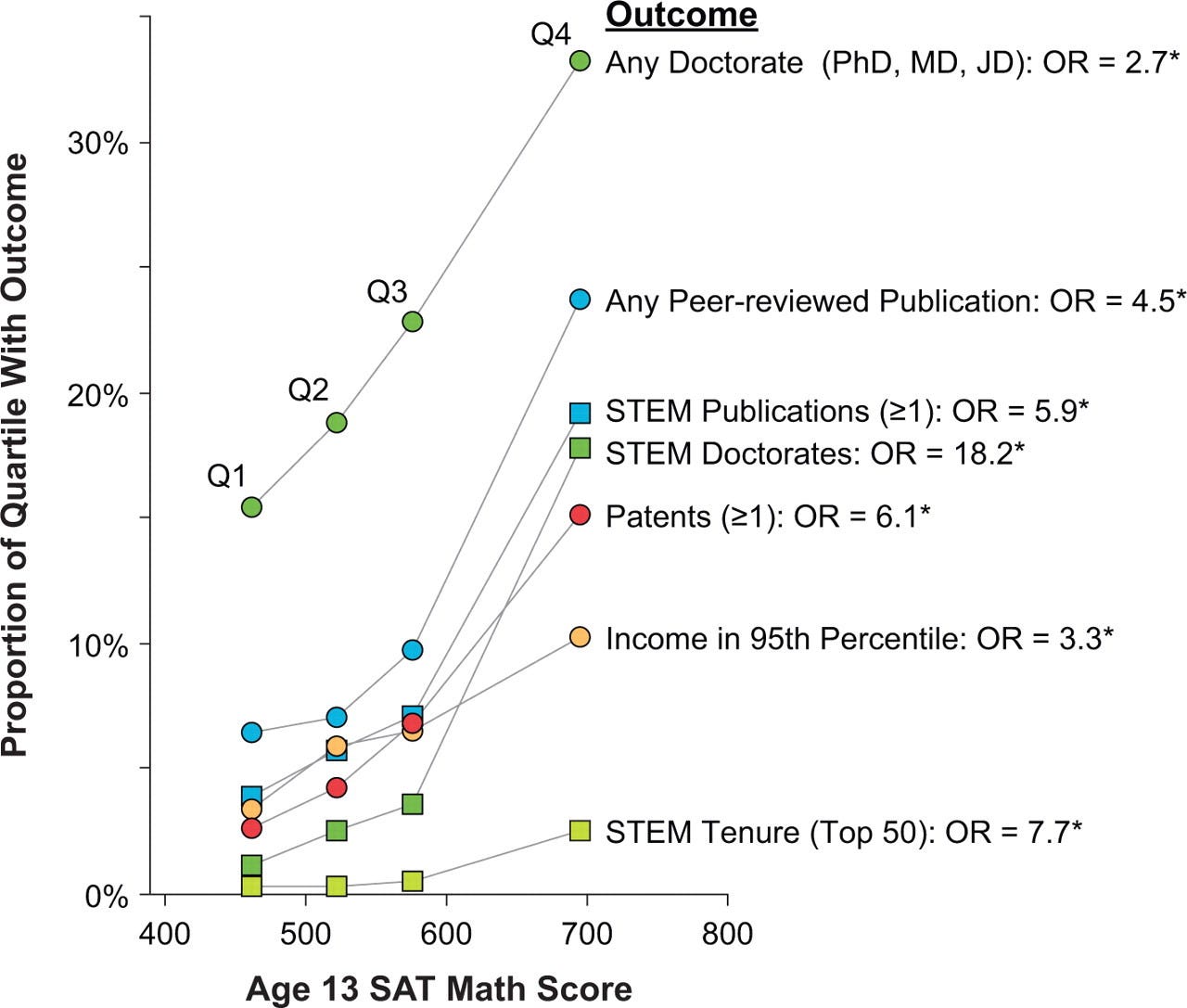

The threshold hypothesis is well known and well loved - but it also appears to be false. The graph below comes from one of the largest studies to address this issue. It shows the accomplishments of people identified at age 13 as among the top 1% in mathematical ability. (Mathematical ability is tightly correlated with IQ.) As you can see, greater ability predicts higher achievement, even at these lofty heights.

The graph comes from a review paper by Kimberley Ferriman Robertson, Stijn Smeets, David Lubinski, and Camilla Benbow. I’ve posted the abstract below. Note that the paper also looked at whether interests and lifestyle preferences predict occupational choices - and sex differences in occupational choices - among the top 1%. (They do.)

The assertion that ability differences no longer matter beyond a certain threshold is inaccurate. Among young adolescents in the top 1% of quantitative reasoning ability, individual differences in general cognitive ability level and in specific cognitive ability pattern (that is, the relationships among an individual’s math, verbal, and spatial abilities) lead to differences in educational, occupational, and creative outcomes decades later. Whereas ability level predicts the level of achievement, ability pattern predicts the realm of achievement. Adding information on vocational interests refines prediction of educational and career choices. Finally, lifestyle preferences relevant to career choice, performance, and persistence often change between ages 25 and 35. This change results in sex differences in preferences, which likely have relevance for understanding the underrepresentation of women in careers that demand more than full-time (40 hours per week) commitment.

You can request a free copy of the Ferriman Robertson paper here.

For more evidence against the threshold hypothesis, see this paper (request a free copy here).

And for a counterpoint, see this paper (free copy here).

I love writing the Nature-Nurture-Nietzsche Newsletter - but it’s a lot of work! If you can afford it, please consider a paid subscription. You’ll get access to all my new posts and the full archive - and you’ll also make it possible for me to continue writing!

All the best,

Steve

I first read your post on the top 1% and then stumbled upon Erik Hoel's post, which also uses the same graph but is really sceptical about it: https://www.theintrinsicperspective.com/p/iq-discourse-is-increasingly-unhinged

In his post, Hoel writes that, for example, the study "Who rises to the top?" is methodologically flawed because it didn't "merely [track] students without interference, impartially noting their future amazing accomplishments" but "an overwhelming majority of participants (95%) took advantage of various forms of academic acceleration in high school or earlier to tailor their education to create a better match with their needs".

What do you make of this, and how does it affect your view of the subject?

What’s fascinating is that one never sees studies of extremely high performing people, at an early age, who were prevented from being allowed exceptional educational opportunities.

One of the fascinating features of “Young Sheldon” was that the character was encouraged and supported at every opportunity in his spectacular abilities.

I tend to believe that to a degree non-conforming intelligence can be actively suppressed.

One other interesting point in the study you mentioned is their call out of women and intelligence.

One would think that women evolved staggering intelligence owned the last few decades based on their achievement and educational performance compared with decades prior.

I think the STEM debate is such a red herring…