Who's More Biased, Left or Right?

In politics, both sides think the other is biased - and both sides are right

Tis the season once again! As an early Christmas present, I’d like to rerelease this earlier paid post as a free post for everyone. It’s about one of my favorite papers of the last few years: a 2018 meta-analysis looking at partisan bias and whether it’s stronger on one side than the other. Hope you enjoy it - and Merry Christmas to all who celebrate!

The Big Picture

When it comes to politics, both sides think the other side is more biased than their own. Liberals think that conservatives are more biased; conservatives think that liberals are more biased.1

Is either side actually right? Many social scientists would say yes, liberals are right: Conservatives are generally more biased.

At the same time, plenty of research in psychology suggests that no one is immune to motivated reasoning and other cognitive distortions, and thus that we might expect to find partisan bias on both sides of the political aisle.

Psychologist Peter Ditto and colleagues conducted a thorough meta-analysis to try to settle the issue once and for all. Their results strongly supported what they called the symmetry hypothesis: Not only are both sides biased, but both are about as biased as the other.

Ironically, the fact that many researchers studying partisan bias have been adamant that conservatives are more biased than liberals seems to be an example of partisan bias.

That’s the big picture; now, let’s dig into the details…

Both Sides Think the Other Side is Biased

2024 is a big year for democracy. According to Time Magazine, more people will go to the polls this year than in any prior year in history. In fact, nearly half the world’s population will have the opportunity to vote before New Years Eve 2024.

To my mind, and I hope yours too, this is great news; aside from anything else, it’s a reminder of just how many nations now have at least a semblance of democratic rule. At the same time, though, election years always bring to the fore one of our less admirable traits as a species: our propensity for partisan bias.

Partisan bias comes in many shapes and sizes, but at its core, it can be defined as “a general tendency for people to think or act in ways that unwittingly favor their own political group or cast their own ideologically based beliefs in a favorable light.” I imagine most of us would agree that people on both sides of the political spectrum are sometimes guilty of this form of bias. But is one side guiltier than the other? In other words, is one side more prone to partisan bias? That’s the question that Peter Ditto and colleagues set out to answer in their fascinating 2018 paper.

In a sense, there’s already a near-consensus on this issue: Almost everyone agrees that one side definitely is more biased than the other. The problem, though, is that people disagree about which side this is: Conservatives think it’s liberals; liberals think it’s conservatives. As Ditto and co. note,

A few hours watching cable news or reading accounts of political events on any of hundreds of partisan websites will reveal a pervasive narrative in which political allies are characterized as rational, informed, and reasonable, whereas political opponents are described as irrational “low-information voters” blinded by partisan bias. These recriminations are distinctly mutual, to the point that politicians and pundits from both the left and right rely on the same colorful phrases to capture how the other side is “drinking the Kool-Aid” or suffering from one form or another of “derangement syndrome.”

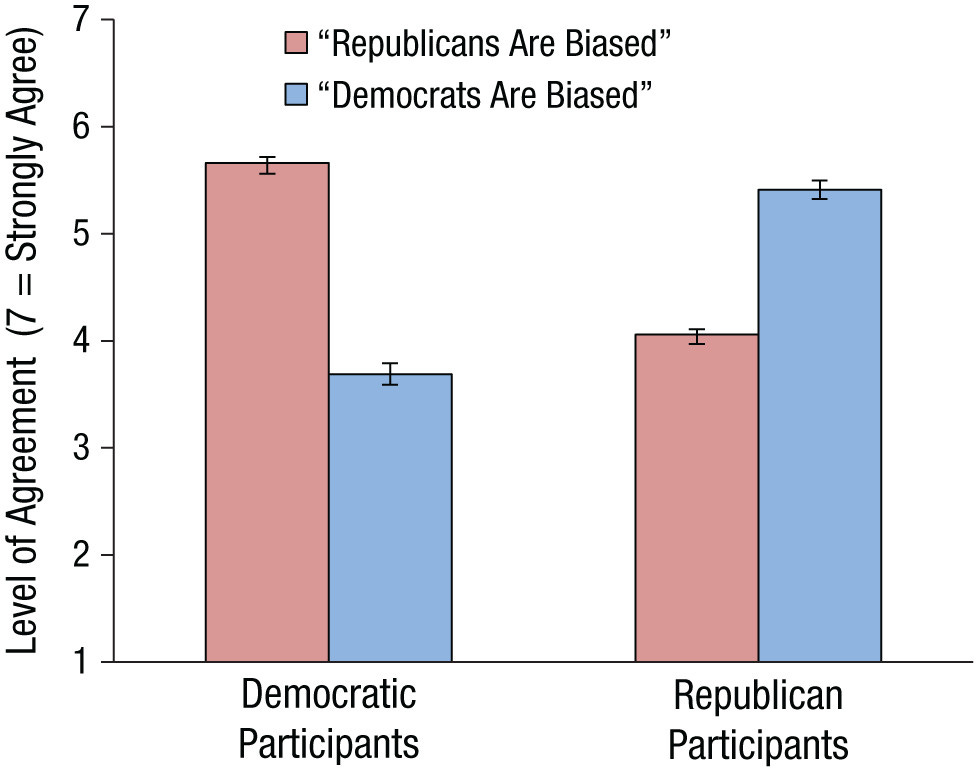

In case you want more rigorous evidence for these mutual recriminations, Ditto and colleagues surveyed nearly 1,000 U.S. citizens, and found - as expected - that partisans on both sides think the other side is more biased than their own.

Who’s Right?

At first glance, we might assume that we’re looking at just another example of partisan bias - specifically, partisan bias in the attribution of partisan bias. It is possible, however, that one side or the other is right. Do we have any reason to think that they might be?

Many social scientists would answer in the affirmative. Conservatives, they’d argue, are more dogmatic and less scientifically-minded than liberals, and therefore more likely to discard evidence that doesn’t mesh with their political views. Liberals, in contrast, are less likely to discard evidence, not only because they’re more flexible and open-minded, but also because their political views were shaped by the evidence in the first place. Thus, many social scientists would argue that conservatives are more biased than liberals. (It’s only fair to point out that most social scientists fall on the liberal side of the political ledger.)

But although the idea that conservatives are more biased is common in the social sciences, the issue is far from settled. Plenty of research in psychology suggests another possibility: Because all human beings are prone to motivated reasoning and ingroup-outgroup bias, and because people on both sides of the political aisle are human beings, people on both sides will be similarly prone to bias.

Thus, the scientific literature suggests two main hypotheses: an asymmetry hypothesis (conservatives are more biased than liberals) and a symmetry hypothesis (conservatives and liberals are about equally biased). Of course, a third possibility is that liberals are more biased than conservatives. Few if any social scientists have championed this position; however, conservatives might argue that this is mainly because most social scientists are liberals, rather than because they’ve explored the possibility and found it wanting. So, we should keep this third hypothesis in mind as well.

What Does the Research Say?

To adjudicate the issue, Peter Ditto and colleagues tracked down every study they could find on the topic of partisan bias, and synthesized them using a procedure known as meta-analysis. They focused on a specific type of partisan bias, namely the tendency to evaluate information more favorably when it supports your own side than when it goes against it. Ultimately, they located 51 studies canvassing more than 18,000 participants - enough, I’d argue, to make for a very persuasive study.

The table below shows the main results. The critical column is the r column; this shows the level of partisan bias for the full sample, and for liberals and conservatives separately. It also shows the difference in levels of bias for liberals vs. conservatives. If the r value has asterisks next to it, that means it’s statistically significant, and thus that we can tentatively accept it as a real effect. If it doesn’t, it’s not and we can’t.

There are two main findings to notice. The first is that people on both sides are prone to partisan bias, seeing information that flatters their political preferences as more plausible than information that rudely contradicts them.

The second and more important finding is that both sides are about as biased as the other. You might notice that the estimated level of bias in the table is slightly higher for conservatives. That difference, however, isn’t statistically significant (see the final r value). This means that we have to treat it as if it’s no real difference at all. Our tentative conclusion, then, should be that liberals and conservatives are equally prone to bias.

How Robust is the Finding?

To assess the robustness of the finding, Ditto and colleagues examined whether it held up across different types of participants, different types of studies, and different political issues. The results are shown in the following table. The column to focus on this time is the rdiff column: the one in the middle. This shows the difference in levels of bias for liberals vs. conservatives for each of the variables listed on the left. Once again, asterisks indicate statistical significance, and the absence of asterisks indicates the absence of significance.

The key finding is that, regardless of the details of the study, conservatives and liberals come out as equally biased. It doesn’t matter how you measure political orientation; it doesn’t matter whether the study looks at bias based on the source of information or the content; it doesn’t matter whether the study involves a student sample, an online sample, or a nationally representative sample; it doesn’t matter whether the topic is abortion, the environment, or whatever else; and it doesn’t matter whether the study looks at bias in response to scientific data or other information (e.g., policies or politicians’ behavior). In every case, both sides are biased, and both are biased to a similar degree.

I should mention that there were relatively few participants in some of the subgroups in this analysis. Still, the analysis should nudge up our confidence that the symmetry finding is robust, and that it’s applicable to a wide range of people and circumstances.

Was There Any Evidence of Publication Bias?

As a further test of the robustness of their results, Ditto and colleagues checked for publication bias - that is, the tendency to report or publish only those results consistent with one’s preferred hypothesis.

Now, you might be wondering why they bothered; after all, publication bias would presumably have favored studies showing that conservatives are more biased than liberals, and the meta-analysis didn’t find that. However, it’s possible that liberals are actually more biased than conservatives, but that publication bias obscured this difference.

The good news, though, is that this wasn’t the case. There was no evidence of publication bias for studies showing conservative bias - or, for that matter, liberal bias. This should again nudge up our confidence in the validity of the results.

What’s the Takeaway?

In summary, then, both sides are 100% correct in assuming that the other side is biased. The only place they go wrong is in assuming that their own side is relatively immune.

In light of these findings, it’s curious that so many social scientists have been so convinced that conservatives are uniquely prone to partisan bias. The obvious explanation is that the scholars studying partisan bias are just as prone as anyone else to the pathology they study, and that the research on partisan bias has - rather ironically - been distorted by partisan bias.

Ditto and colleagues summed up their findings as follows.

It is common in political discourse to hear politicians and pundits contrast the biased opinions of their political opponents with their own side’s impartial view of the facts. Our meta-analysis suggests instead that partisan bias is a bipartisan problem and that we may simply recognize bias in others better than we see it in ourselves. This same myopia toward our own side’s biases may also help explain why a field dominated by liberal researchers has been so much more focused on the biased perceptions of the political right than the political left…

Together with a growing body of evidence suggesting that increased knowledge and expertise in a topic area exacerbates rather than ameliorates political bias, the prognosis for eradicating partisan bias with harder data and better education does not seem particularly rosy.

Sophisticated strategies informed by psychological science need to be developed to combat our political prejudices and to begin to build a less polarized, more civil, and more evidence-based political culture. The evidence available right now, both scientific and anecdotal, suggests that this will not be easy. But a crucial first step is to recognize our collective vulnerability to perceiving the world in ways that validate our political affinities.

Follow Steve on Twitter/X.

Thanks for reading - and if you enjoyed this free post, please spread the word and help support my efforts to promote politics-free psychology!

Further Reading

You can read a free copy of the Ditto meta-analysis here.

You can read a critique of the paper here.

And you can read a response to the critique from the original authors here.

From the Archive

I’m using the U.S. nomenclature here, where liberals means more or less “people on the left of the political spectrum.”

I enjoyed reading this. Of course, I’m biased 😉. Thanks for another evidenced article, Steve.