“I’m concerned about trigger warnings’ rapid spread, despite a complete lack of evidence they help... We should be talking about things that matter more [like] how to encourage people to access evidence-based care for PTSD.”

Trigger warnings are statements alerting people that a lecture, a reading, or other content contains material that could be upsetting, especially to trauma victims. Once confined to the academy, trigger warnings have long since escaped into the wider world, and are now familiar to almost everyone and almost everyone’s dog. Most people know what they are, and most people know what they’re for. Not only that, but anyone who’s paid even the slightest attention to the issue knows that, although some people are extremely enthusiastic about trigger warnings, others have serious misgivings. I belong to the latter camp.

Much has been written about the topic over the last decade, by defenders and detractors alike. My aim in this post is to pull together the best arguments I’ve seen across multiple works, and settle the debate once and for all. With the publication of this article, nothing will need to be written on the topic again.

I’m joking, of course - but I do hope that the piece will persuade at least some people that trigger warnings are well-intentioned but ultimately harmful. Let’s get to it, then: 10 arguments against trigger warnings!

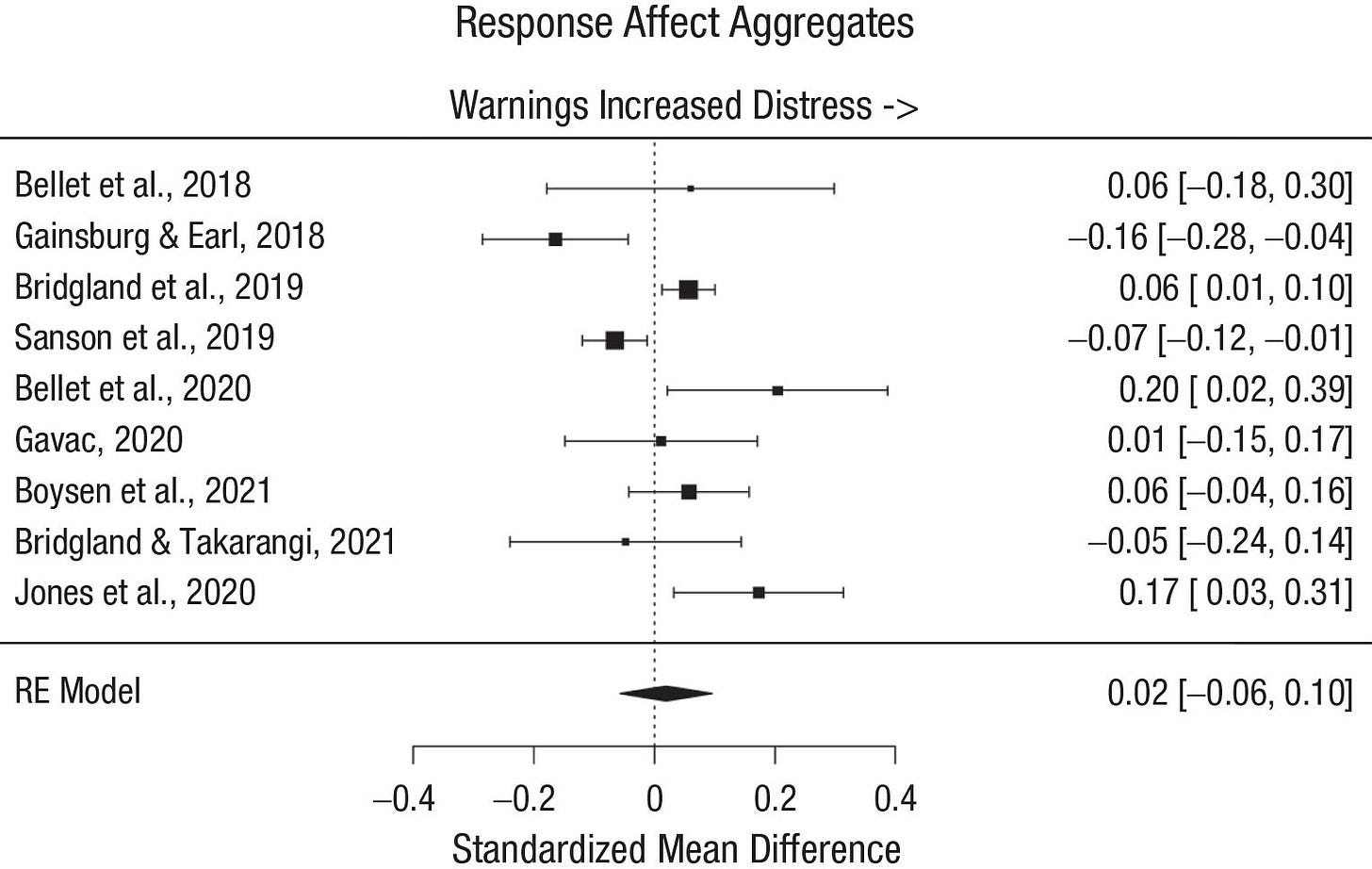

1. Some argue that trigger warnings help trauma victims and others to emotionally prepare for upsetting material. Knowing that it’s coming, people can brace themselves for it. Others, however, argue that trigger warnings instead increase distress in response to the material, on the assumption that if you tell people “you might find this material upsetting,” they’ll find it more upsetting than they otherwise would.

Who’s right? According to the gold-standard meta-analysis on the topic, neither side is! Trigger warnings have no reliable effect in either direction.

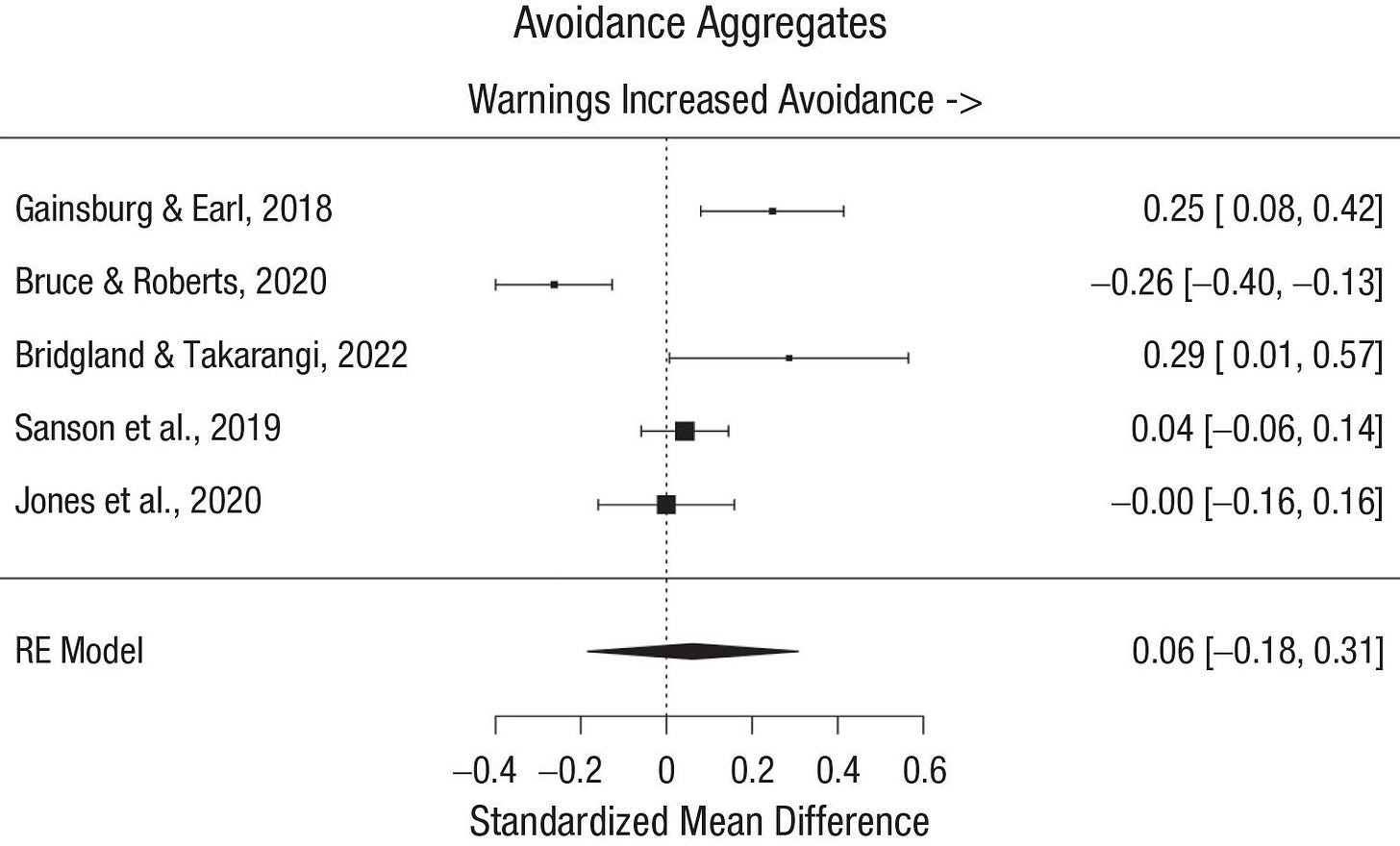

2. Some argue that trigger warnings are useful because they give people - trauma victims in particular - the option to avoid upsetting material. Others, however, argue that although trigger warnings do indeed do that, this is a bad thing rather than a good thing because avoidance helps maintain trauma. Trigger warnings may therefore be countertherapeutic.

Who’s right? Again, the answer may be neither side. The preponderance of evidence suggests that trigger warnings don’t reliably lead people to avoid potentially upsetting material, rendering the whole debate moot.

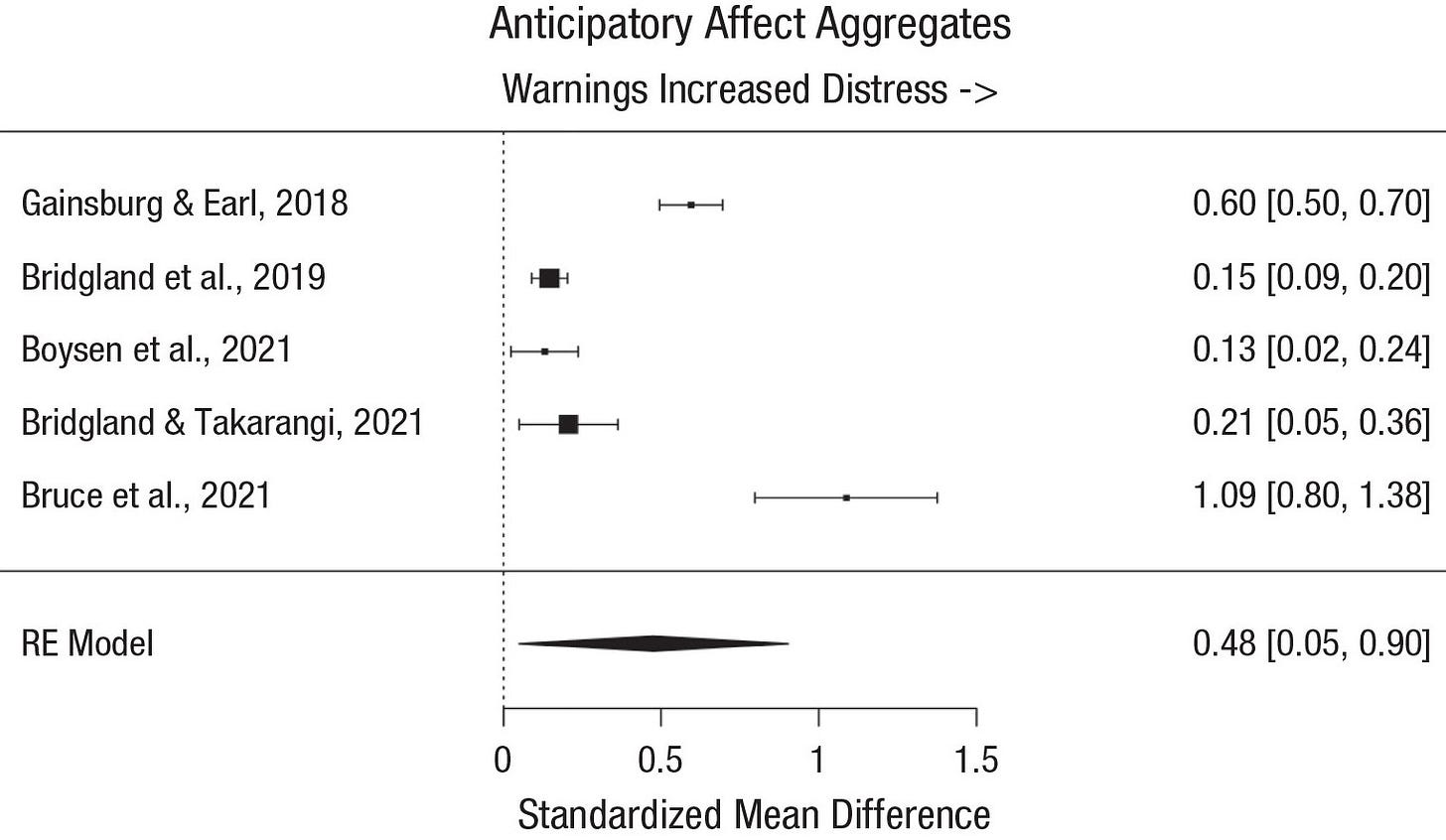

3. By now you might be wondering whether trigger warnings have any effect at all. The answer is yes. One thing they reliably do is increase anticipatory anxiety - that is, they make people more anxious about the prospect of encountering the material. When they actually do encounter it, they’re no more upset than they would have been - and no less. They were just more stressed out in the lead up.

4. A common refrain at this point is that although trigger warnings don’t seem to help, they’re also not especially harmful. Why, then, not just use them? There are many reasons not to. For starters, as one of the big names in the area, Payton Jones, noted in a thread on Twitter/X:

In the same vein, Jones has also said that “you should never do anything that doesn’t work, period, even if it doesn’t do harm. If it’s not actively helping, encouraging its use would essentially be engaging in clinical pseudoscience.”

5. Furthermore, even if trigger warnings don’t increase distress in response to upsetting material, and even if they don’t lead to the avoidance of that material, they could nonetheless do harm in other ways. To begin with, the use of trigger warnings could bolster the misguided view that people who’ve experienced traumatic events are inevitably scarred by them and psychologically fragile forever more, and it could reinforce trauma victims’ belief that their trauma is central to their identity. As Jones and colleagues note:

In reality, a majority of trauma survivors are resilient, experiencing little if any lasting psychological changes as a result of their experience. Aggregated across various types of trauma, just 4% of potentially traumatic events result in PTSD. However, trauma survivors who view their traumatic experience as central to their life have elevated PTSD symptoms. Trauma centrality prospectively predicts elevated PTSD symptoms, whereas the reverse is not true. Decreases in trauma centrality mediated therapy outcomes.

In short, not only do trigger warnings not help trauma victims, they may even make things worse. As the law professor Jeannie Suk Gersen noted in The New Yorker, “The perverse consequence of trigger warnings, then, may be to harm the people they are intended to protect.”

6. Trigger warnings could also be harmful for the same reason that homeopathic remedies can be: because they distract us from interventions that might actually work. If you’d genuinely be traumatized by the content of a university course, you don’t need a trigger warning; you need therapy. This might sound dismissive, but I don’t mean it that way; therapy is great for people who need it - and people with that level of trauma need it. As Sarah Roff noted in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Students with unusually intense responses to academic cues should be referred to student-health services, where they can be evaluated and receive evidence-based treatments so that they can participate fully in the life of the university.

7. Over and above any clinical harms, trigger warnings could harm students’ education. As Amna Khalid and Jeffrey Snyder observed in The Chronicle:

We found no evidence that trigger warnings improve students’ mental health. What’s more, we are now convinced that [trigger warnings] push students and faculty members alike to turn away from the study of vitally important topics that are seen as too “distressing”…

On campus the definition of what constitutes a trigger has expanded dramatically from stimuli that induce symptoms of PTSD to any material that might elicit “difficult emotional responses”… [P]olicies like these would impede meaningful engagement with difficult topics... Indeed, embracing trigger warnings may drive some students to be on high alert for any content that might possibly upset or offend…

In our view, the problems with trigger warnings extend well beyond mental-health concerns. By contributing to a misguided safety-and-security model of education, trigger warnings ultimately deprive all students of the most powerful learning opportunities.

8. More specifically, trigger warnings could impede the discussion of politically charged topics – topics that, almost by definition, are among the most important to discuss. A statement by the American Association of University Professors captured the problem well:

The presumption that students need to be protected rather than challenged… is at once infantilizing and anti-intellectual. It makes comfort a higher priority than intellectual engagement… [I]t singles out politically controversial topics like sex, race, class, capitalism, and colonialism for attention. Indeed, if such topics are associated with triggers, correctly or not, they are likely to be marginalized if not avoided altogether by faculty who fear complaints for offending or discomforting some of their students… In this way the demand for trigger warnings creates a repressive, “chilly climate” for critical thinking in the classroom.1

9. The harms of trigger warnings may also extend beyond the classroom. Here’s another excerpt from Khalid and Snyder:

Alas, the content that is most likely to raise hackles is often of the utmost importance. As the Harvard law professor Jeannie Suk Gersen reported in 2014, about a dozen of her colleagues at multiple institutions had dropped rape law from their criminal-law courses because students were complaining the material was “triggering.” Consider the consequences: Not only will students not learn the material, but there will be fewer lawyers with the expertise to fight for rape victims.

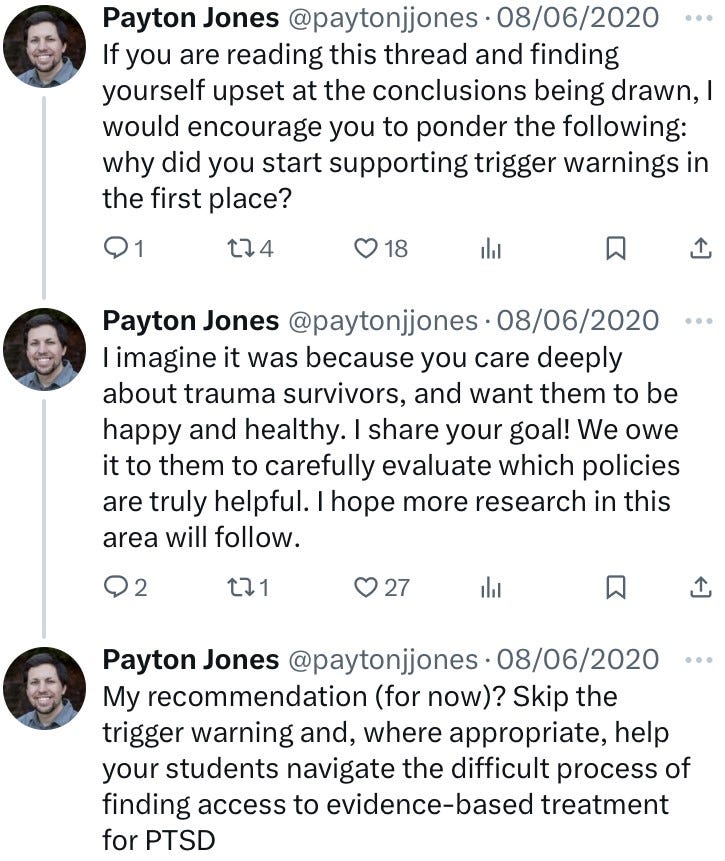

10. Unfortunately, because trigger warnings have been caught up in the culture war, some people are reluctant to criticize or abandon them. Indeed, some may be upset by the idea that they don’t work, and see it as a regressive attack on progressive efforts to make the world a better place. On this point, I’ll give the last word to Payton Jones, who said the following in another of his epic threads on Twitter/X:

This post was free to read for all, so feel free to share it with friends or on social media.

Follow Steve on Twitter/X.

Upgrade to a Premium Subscription

If you’d like to support my work, consider upgrading to a premium subscription. With a premium subscription, you’ll get:

Full access to all new posts and the archive

Full access to exclusive features such as my “12 Things Everyone Should Know” posts, Linkfests, and other regular features

The ability to post comments and interact with the N3 Newsletter community.

Your support helps keep this newsletter going. Thanks!

Steve

Related Reading From the Archive

Reforming DEI

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives have come under increasing fire in recent months, with critics charging that, although many of the goals of the movement are good, the specific ways in which they’re being pursued are often illiberal, counterproductive, and damaging to the pursuit of knowledge.

Steven Pinker's Five-Point Plan for Saving the Universities

Universities have been having a hard time lately. Once a trusted institution, the last decade has seen a steady erosion in trust. Much of this has been self-inflicted, as universities have become increasingly politicized and censorious. What can be done to stem the tide? In a recent essay in

For those thinking “Yes, but students like them,” a new preprint suggests that trigger warnings have no positive impact on perceptions of instructors or the classroom environment.

I believe the real purpose of trigger warnings is to communicate that the listener/viewer should disagree with the subsequent statements without having to actually engage with the arguments being made. Once someone decides that a speaker is wrong, they stop listening. Trigger warnings ensure this happens before the speaker even starts talking.

Teacher friends have reported to me that some historical facts have been deleted out of the curriculum due to fears of “triggering” certain students. Unbelievable.