People vs. Things: Why Men and Women Choose Different Jobs

The Swiss apprenticeship study that explains the gender job gap

In Case You Missed It…

One of the most robust findings in psychology is that men and women have somewhat different career-related interests: On average, men are more interested in working with things, whereas women are more interested in working with people. A fascinating analysis of the apprenticeship system in Switzerland shows how these preferences help shape young people’s real-world occupational choices.

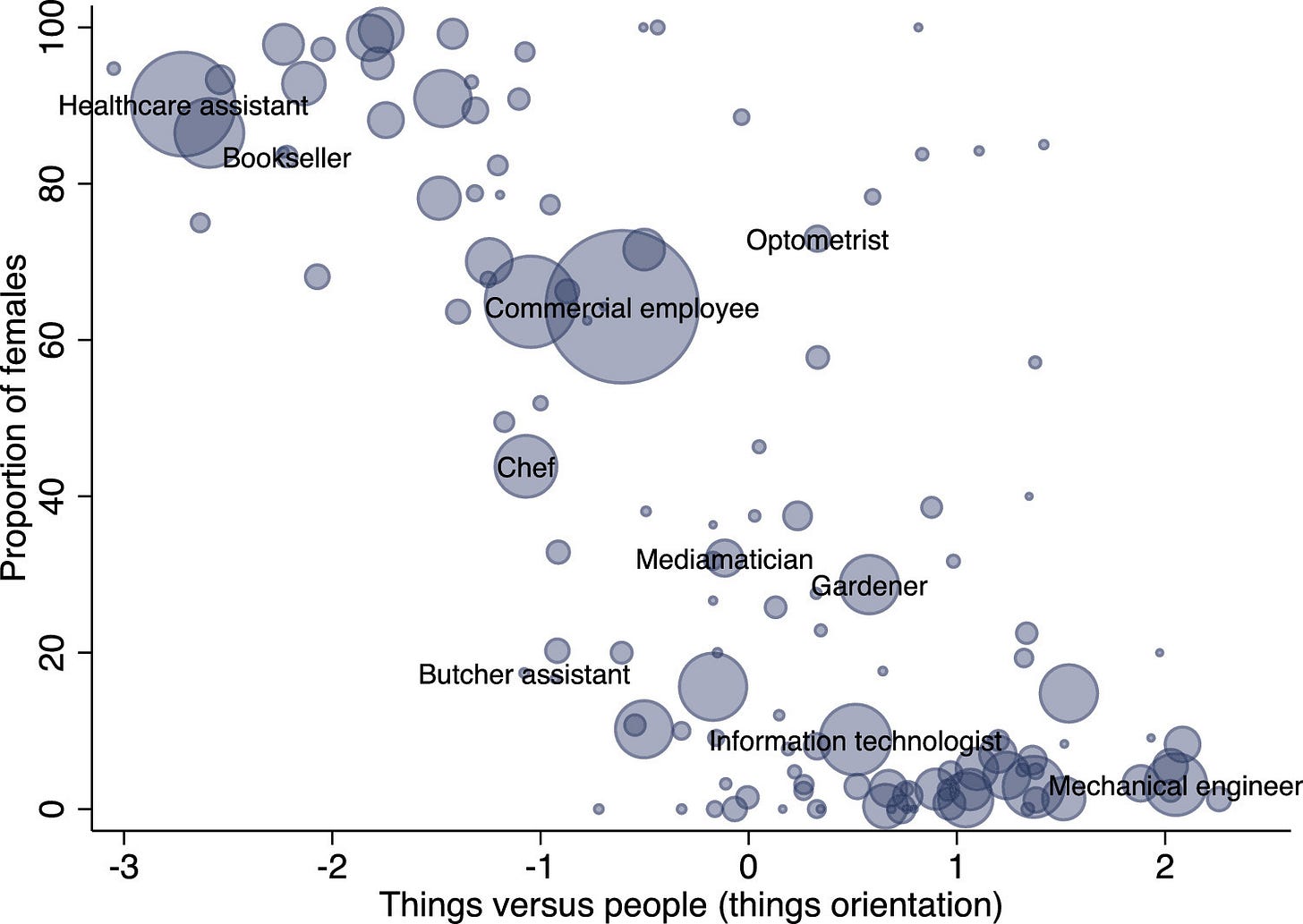

Andreas Kuhn and Stefan Wolter examined 130 apprentice occupations. Whereas most studies in the area look at people’s expressed occupational interests, this one looked at the nature of the occupations themselves - specifically, where each falls on the people-things dimension. Jobs involving machines, materials, and tools sat at one end; jobs involving care, communication, and social interaction sat at the other. The researchers then plotted each occupation’s position on this spectrum against the proportion of female apprentices.

The results are shown in the graph below. As you can see, the more people-oriented a profession is, the more female-dominated it tends to be, and the more things-oriented it is, the more male-dominated. The effect is extremely strong, making the things-people dimension one of the most powerful known predictors of occupational sex differences.

In a separate analysis, the researchers tracked adolescents’ career aspirations at ages 13 to 15, before they entered the apprenticeship system. Even at that age, boys leaned toward things-oriented occupations, and girls toward people-oriented ones. This implies that the occupational divide can’t be explained solely by employer discrimination or other external barriers, but instead reflects early-emerging differences in vocational interests.

Kuhn and Wolter’s findings raise important questions regarding efforts to close the gender gap in STEM. Every push to get more women into things-related fields is simultaneously a push to get them out of equally important people-related fields such as healthcare and education - fields that, on average, they tend to prefer. We’re therefore faced with a decision: Should gender equality mean identical outcomes, or identical freedom to follow one’s interests?

I’ll be discussing these issues in depth in my forthcoming book, A Billion Years of Sex Differences - available for preorder here!

Follow me on Twitter/X for more psychology, evolution, and science.

Further Reading

I’ve written several academic papers with Lewis Halsey on the question of sex differences in STEM representation.

The main one is this 2021 paper in the European Journal of Personality:

Stewart-Williams, S., & Halsey, L. G. (2021). Men, women and STEM: Why the differences and what should be done? European Journal of Personality, 35, 3-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890207020962326 [Free version]

This was published alongside two commentaries - one favorable; one less so.

Ceci, S. J., Kahn, S., & Williams, W. M. (2021). Stewart-Williams and Halsey argue persuasively that gender bias is just one of many causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. European Journal of Personality, 35, 40-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890207020976778

El-Hout, M., Garr-Schultz, A., & Cheryan, S. (2021). Beyond biology: The importance of cultural factors in explaining gender disparities in STEM preferences. European Journal of Personality, 35, 45-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890207020980934

Here’s our response to the less-than-favorable commentary:

Stewart-Williams, S., & Halsey, L. G. (2022). Not biology or culture alone: Response to El-Hout et al. (2021). European Journal of Personality, 36, 991–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070211022477 [Free version]

See also this summary of our work on the topic by the biologist Jerry Coyne.

How You Can Support the Newsletter

If you want to support my efforts to bring you non-politicized psychology, there are several ways you can do it.

Like and Restack: Click the buttons at the top or bottom of the page to boost the post’s visibility on Substack.

Share: Send the post to friends or share it on social media.

If You Can Afford It, Upgrade to a Paid Subscription: A paid subscription will get you:

Full access to all new posts and the archive

Full access to excerpts from my forthcoming book A Billion Years of Sex Differences (preorder here)

Full access to exclusive content such as my “12 Things Everyone Should Know” posts, Linkfests, and other regular features

The ability to post comments and engage with the N3 Newsletter community.

If you could do any of the above, I’d be hugely grateful. It’s the support of readers like you that makes this newsletter possible.

Thank you!

Steve Stewart-Williams

I guess this sort of study is necessary to affirm lifelong observations all of us, excepting Blank Slate dogmatists, have.

Job preferences could be at the heart of the much-talked-about declining fortunes of men. Dirty, dangerous jobs like coal mining are in decline while human oriented jobs are on the rise. It’s not as if all men are attracted to the dirty, dangerous jobs, but many men are probably unmotivated to pursue jobs that require a ton of interpersonal interaction.